How to Write the Chinese Symbol for Water – A Step-by-Step Guide

The symbol for water in Chinese is represented by the character 水 (shuǐ). This character originates from ancient scripts like the Oracle Bone Script and Seal Script, where it pictorially depicted flowing water.

Structurally, it consists of three strokes symbolizing ripples. In Chinese philosophy, particularly Daoism and Confucianism, water signifies purity, adaptability, and the essence of life.

It is commonly featured in idioms and traditional ink paintings to convey tranquility and harmony. In modern contexts, the character is used in branding and digital interfaces to evoke qualities of fluidity and clarity.

Understanding the evolution and uses of 水 opens doors to deeper cultural insights.

Key Takeaways

- The Chinese character for water is 水, pronounced "shuǐ."

- Ancient forms include Oracle Bone Script, Bronze Script, and Seal Script.

- It represents flowing streams and ripples in its pictographic origins.

- Water symbolizes purity, adaptability, and life essence in Chinese culture.

- Proper stroke order is crucial for writing the character accurately.

Origins of the Character

Tracing the origins of the character for water in Chinese, known as 水 (shuǐ), reveals a rich historical and etymological journey that dates back to ancient Chinese script forms such as Oracle Bone Script and Seal Script.

The character's evolution reflects the significance of water in Chinese culture, economy, and daily life. Early depictions were pictographic, capturing the essence of flowing streams or rivers. Over time, these depictions transformed into more abstract representations while retaining their fundamental meaning.

The character's structure, comprising three strokes, symbolizes ripples or movement, embodying the dynamic nature of water. This historical progression underscores the profound connection between natural elements and linguistic expression in Chinese, offering insights into the civilization's values and environment.

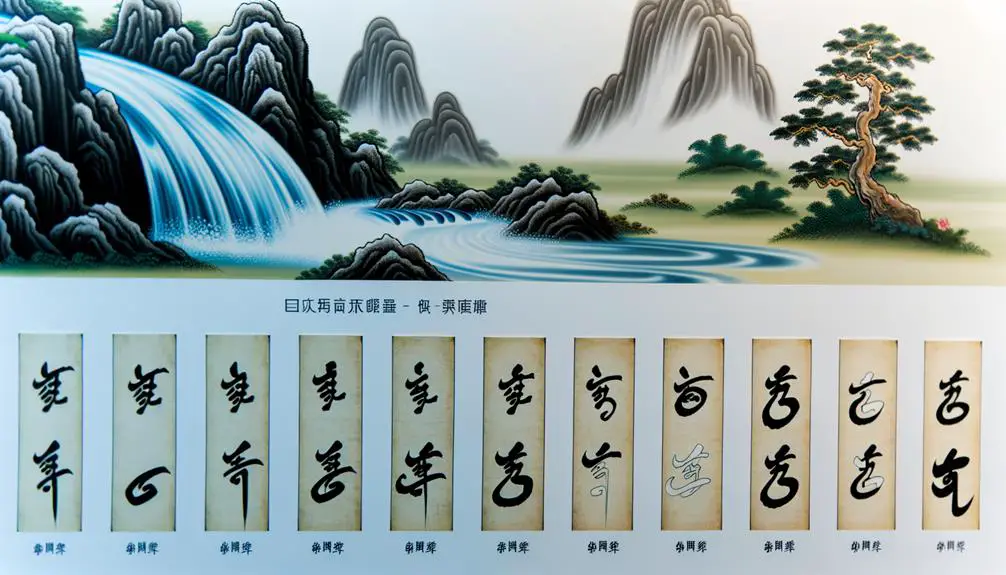

Ancient Script Forms

Ancient script forms, such as Oracle Bone Script, Bronze Script, and Seal Script, provide invaluable insights into the early visual and symbolic representation of the Chinese character for water (水, shuǐ).

Oracle Bone Script, dating back to the Shang dynasty, features a rudimentary depiction resembling flowing water.

The Bronze Script, used during the Zhou dynasty, presents a more stylized yet recognizable form, often found on ritual bronzes.

Seal Script, standardized during the Qin dynasty, exhibits a refined, symmetrical design that paved the way for modern iterations.

Each of these ancient scripts not only reflects the aesthetic and functional evolution of the character but also underscores the cultural and historical significance of water in Chinese civilization.

Evolution Over Time

The symbol for water in Chinese has undergone significant transformation from its ancient script forms to the modern simplified versions used today. Originally depicted through intricate, pictographic representations, the character has been streamlined over centuries to accommodate ease of writing and standardization.

This evolution reflects broader linguistic reforms and societal shifts aimed at enhancing literacy and communication efficiency.

Ancient Chinese Characters

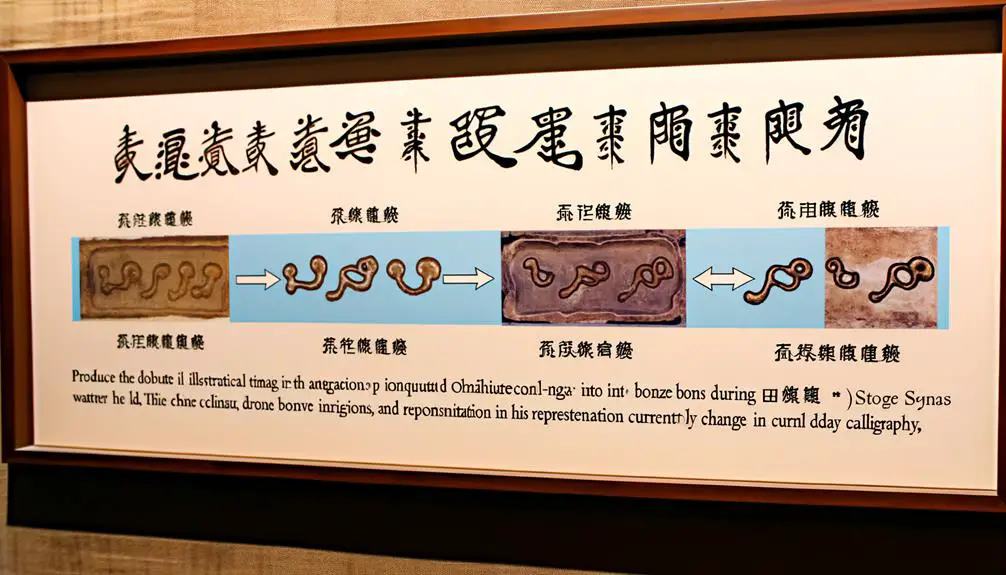

An examination of the evolution of the Chinese character for water reveals significant transformations from its earliest inscriptions on oracle bones to its current standardized form.

Initially, the character for water, 水 (shuǐ), appeared as a series of wavy, flowing lines etched into oracle bones during the Shang Dynasty (c. 1600-1046 BCE). These archaic forms symbolized the natural flow and movement of water.

As Chinese script evolved through the Zhou Dynasty (c. 1046-256 BCE) and beyond, the character underwent gradual stylization and abstraction. By the time of the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BCE), the character had adopted a more simplified, structured form, which laid the groundwork for its present-day appearance.

This historical progression underscores the dynamic nature of Chinese script development.

Modern Simplified Form

Tracing the character for water, 水 (shuǐ), through the modern era reveals significant refinements and adaptations that align with the broader evolution of Chinese script towards greater simplicity and efficiency.

Initially complex, the character underwent a series of systematic changes, particularly during the 20th century, when the Chinese government implemented script reforms to enhance literacy.

The modern simplified form of 水 retains the core elements of its ancient predecessor while eliminating extraneous strokes, thereby facilitating easier learning and faster writing. This transformation is emblematic of the overarching reform movement aimed at streamlining Chinese characters without compromising their semantic integrity.

Consequently, 水 (shuǐ) stands as a tribute to the dynamic, evolving nature of the Chinese written language.

Cultural Significance

Water, represented by the Chinese character 水 (shuǐ), holds profound cultural significance in Chinese philosophy, art, and daily life. Historically, water has symbolized purity, adaptability, and the essence of life.

In traditional Chinese ink paintings, water is often depicted to convey tranquility and the relentless passage of time. The character 水 is also integral in various idioms and expressions, reflecting its importance in communication.

Additionally, water-related rituals and festivals, such as the Dragon Boat Festival, underscore its societal relevance. In Chinese gardens, water features are meticulously designed to create harmony and balance, embodying the principles of Feng Shui.

Therefore, the cultural importance of 水 extends beyond mere symbolism, permeating numerous aspects of Chinese heritage and everyday practice.

Water in Chinese Philosophy

In Chinese philosophy, the concept of water (水) is deeply intertwined with Daoist and Confucian thought, symbolizing qualities such as humility, persistence, and the ability to nourish life without contending.

Daoism, founded by Laozi, extols water for its yielding nature and its capacity to flow around obstacles, embodying the principle of wu wei, or effortless action. Water exemplifies the Daoist ideal of adapting to circumstances without force.

Confucianism, while primarily concerned with social harmony and ethics, also regards water as a metaphor for moral virtue and integrity. Confucius himself admired water for its ability to benefit all things without exerting, reflecting the Confucian virtue of benevolence.

Hence, water's symbolism pervades Chinese philosophical thought as a representation of natural harmony and moral excellence.

Water in Chinese Art

Chinese art, spanning millennia and encompassing various mediums, frequently incorporates water as a central motif to convey themes of tranquility, power, and the interconnectedness of natural elements.

In traditional Chinese landscape painting, water is often depicted flowing through mountains and valleys, symbolizing both the dynamic force and serene aspect of nature. The use of ink wash techniques, known as 'shui mo' (水墨), captures the fluidity and essence of water, enhancing the ethereal quality of the artwork.

Additionally, water features prominently in garden design, where ponds and streams are meticulously integrated to reflect harmony and balance. This artistic representation underscores water's crucial role in Chinese aesthetics, mirroring philosophical and cultural reverence for this essential element.

Common Phrases and Proverbs

Proverbs and common phrases in Chinese culture often utilize the symbol of water to convey wisdom, resilience, and the natural flow of life.

For instance, the phrase '滴水穿石' (dī shuǐ chuān shí), meaning 'dripping water penetrates stone,' underscores the power of perseverance and consistent effort.

Another notable saying, '上善若水' (shàng shàn ruò shuǐ), translates to 'the highest good is like water,' reflecting the Daoist philosophy that water exemplifies ultimate virtue through its adaptability and humility.

Besides, '水能载舟,亦能覆舟' (shuǐ néng zài zhōu, yì nàng fù zhōu) highlights the dual nature of water, which can both support and destroy—analogous to the potential influence of public opinion on governance.

Symbolic Meanings

The symbol for water in Chinese, 水 (shuǐ), possesses profound cultural significance, embodying concepts such as fluidity, adaptability, and life itself.

Historically, this character has evolved from ancient pictographs to its current form, reflecting both aesthetic and practical advancements in Chinese script.

This evolution underscores the enduring importance of water within Chinese philosophy, literature, and daily life.

Cultural Significance Explained

In Chinese culture, the symbol for water, 水 (shuǐ), embodies a profound array of meanings that span from purity and life to adaptability and resilience. Water is revered as a crucial force, essential for sustenance and growth, symbolizing the very essence of life.

Its purity is associated with clarity and moral integrity. Additionally, water's ability to change forms—liquid, solid, or gas—mirrors human adaptability and resilience in the face of challenges.

In Daoist philosophy, water exemplifies the concept of wu wei, or effortless action, by illustrating how it flows naturally, finding the path of least resistance. This harmonious nature of water is also integral to Feng Shui, where it balances and enhances energy flows within environments.

Historical Evolution Unveiled

Tracing its roots through millennia, the symbol for water (水) in Chinese script has undergone a fascinating evolution, reflecting the dynamic interplay between linguistic development and cultural symbolism.

Originally depicted in oracle bone script as a series of wavy lines, this symbol has progressed through several stages:

- Oracle Bone Script (c. 1200–1050 BCE): Early forms featured pictographic representations of flowing water, emphasizing its natural essence.

- Seal Script (c. 221–207 BCE): During the Qin dynasty, the character became more stylized and standardized while maintaining its fluid lines.

- Regular Script (c. 200 CE–present): The modern form, characterized by its simplicity and clarity, evolved for ease of writing and reading.

This transformation encapsulates the historical depth and cultural richness embedded in the Chinese language.

Modern Usage

Modern applications of the Chinese symbol for water (水, shuǐ) extend across various fields, including technology, branding, and contemporary art, reflecting its enduring cultural significance.

In technology, the symbol is often incorporated into user interfaces and software designs to denote water-related functionalities, such as weather apps and hydration reminders.

In branding, companies leverage 水 to evoke purity, fluidity, and adaptability, enhancing brand identity and consumer connection.

Contemporary artists frequently integrate 水 into their works to explore themes of nature, transformation, and sustainability.

This multifaceted utilization underscores the symbol's versatility and deep-rooted importance, bridging traditional connotations with modern interpretations.

Consequently, 水 remains a powerful and relevant cultural icon in today's diverse global landscape.

Learning to Write 水

Understanding the proper stroke order is essential when learning to write the Chinese character for water, 水 (shuǐ), as it guarantees both accuracy and fluidity in writing.

Beginners often encounter common mistakes such as incorrect stroke sequencing or misalignment of the character's components.

Addressing these errors early in the learning process can greatly enhance one's proficiency in Chinese calligraphy and written communication.

Stroke Order Basics

Mastering the stroke sequence for writing the Chinese character for water (水) is vital for achieving both accuracy and fluency in Chinese calligraphy. Proper stroke arrangement ensures that your characters are not only aesthetically pleasing but also legible and consistent with traditional forms.

Here are the basic steps:

- First Stroke: Begin with a brief, vertical downward stroke, slightly curved to the left.

- Second Stroke: Draw a longer horizontal stroke from left to right, intersecting the initial stroke.

- Third Stroke: Conclude with two diagonal strokes, one starting from the peak of the vertical stroke and the other from the center, slanting downwards to the right.

Adhering to these stroke sequences is essential for proficiency in writing Chinese characters.

Common Writing Mistakes

Despite the importance of mastering the correct stroke order, beginners often encounter common mistakes when writing the Chinese character for water (水), which can lead to misinterpretation and aesthetic inconsistencies. Incorrect stroke order, uneven stroke length, and improper spacing are frequent errors. These mistakes can distort the character's intended structure and meaning.

| Common Mistake | Description | Resulting Issue |

|---|---|---|

| Incorrect Stroke Order | Strokes drawn out of sequence | Alters the character's form |

| Uneven Stroke Length | Strokes are too long or too short | Affects symmetry and balance |

| Improper Spacing | Strokes are too close or too far apart | Leads to visual misalignment |

Understanding these pitfalls can greatly enhance the accuracy and aesthetic quality of writing 水.

Conclusion

The symbol for water, 水 (shuǐ), embodies not only an essential natural element but also a cornerstone of Chinese culture and philosophy. From its ancient script forms to its evolution over millennia, this character flows through the veins of Chinese language and thought, much like water through a riverbed.

Revered in idioms, proverbs, and modern usage, 水 remains an enduring evidence to the profound relationship between language, nature, and human experience.